How US satellites pinpointed source of missile that shot down airliner

Satellite technology built to detect ballistic missile launches caught Buk’s signature.

An artist's rendering of the SBIRS "High"

geosynchronous infrared surveillance satellite, one of the newer

additions to the DOD's constellation of missile launch detection

satellites.

Lockheed Martin

That information likely came from one of a network of satellites operated by the Air Force and the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO), the US intelligence community’s spy satellite operations agency. Using highly sensitive infrared sensors and other electronic intelligence gathering sensors, these satellites can detect a variety of ground-based missile systems, as well as some aircraft, by their infrared signature. They also carry sensitive electronic intelligence sensors that can detect radar signals associated with anti-aircraft missile systems like the Buk launcher that has been widely pointed to as the culprit in the MH17 downing.

The latest of these satellite systems is the Space Based Infrared System (SBIRS), the successor to the long-running and euphemistically named “Defense Support Program” (DSP) satellite system. The DSP started in the late 1960s and continued in various forms through the last decade. A portion of the DSP constellation of satellites continues to function today and has been considered for use in tracking forest fires and potentially forecasting impending volcanic eruptions.

The unblinking eyes in the sky

In 1995, as the Cold War came to an end and the demands on satellite infrared systems increased, the Air Force launched the SBIRS program. Built under the direction of the US Air Force’s Space and Missile Systems Center’s Infrared Space Systems Directorate, SBIRS was designed for four mission areas:

- Strategic ballistic missile launch warning for the president and the Defense Department leadership

- Theater and strategic missile defense information, to provide early targeting data to systems such as the Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense system aboard US Navy cruisers

- Collecting technical intelligence on potential adversary’s missile systems

- “Battlespace awareness”—real-time information provided to military commanders about infrared “events” that could affect forces in the field and provide data for strike planning against launch systems.

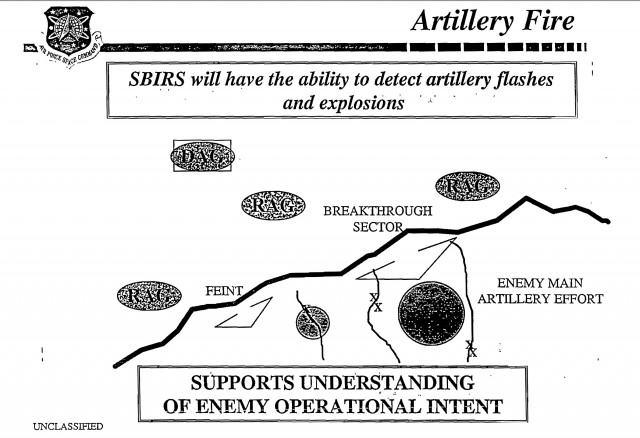

Enlarge /

A slide from a 1998 Air Force Space Command presentation sells SBIRS'

capability to detect artillery flashes to understand where the enemy's

real attack objectives are.

Plan B

But the SBIRS High program ran into repeated trouble. To verify the functionality of SBIRS Low, two NRO signals intelligence satellites launched into highly elliptical orbits in 2006 and 2008. However, a geosynchronous NRO satellite launched in 2007 failed after only 7 seconds in orbit, resulting in further delays.The Air Force SBIRS Low program had similar problems. It was cancelled and resurrected as the Space Tracking and Surveillance System (SSTS) and handed over to the Missile Defense Agency (MDA) as the Bush administration pushed ahead with ballistic missile defense research. Two SSTS satellites were put in orbit in September of 2009. But the MDA decided not to take SSTS any further. A month after the SSTS launches, the MDA kicked off the Precision Tracking Space System program—a program that was killed in 2013.

All the while, existing infrared satellites were expiring, and the Air Force started to explore alternatives to SBIRS. The service continued to launch DSP satellites until 2007, at which point its leadership started looking for a SBIRS alternative. That plan B, the Alternate Infrared Surveillance System (AIRSS) was later renamed the Third Generation Infrared Surveillance (3GIRS) program and was led by Raytheon and defense contractor SAIC. It quickly picked up steam as a lower-cost alternative—it used a “full earth staring sensor” that could watch an entire hemisphere of the planet for infrared plumes. But despite being on track and on budget, 3GIRS was cancelled in 2011 as the first SBIRS geosynchronous satellite was successfully put into orbit.

So far, the DOD has spent $2.35 billion on the SBIRS High satellite program, and it has two satellites in orbit. The SSTS satellites and NRO satellites have exceeded their expected lives but still remain in orbit—as do some later DSP satellites. And they have all been pressed into service for monitoring emerging potential threats, such as the flashpoints on Ukraine’s eastern border.

It's for that reason that NRO and Air Force satellite assets were most likely watching the area near Donetsk, Ukraine, yesterday as an anti-aircraft battery launched a single missile at the Malaysian Airlines Boeing 777, bearing witness to a tragedy that no missile defense system was ever intended to thwart.

No comments:

Post a Comment